|

We wanted to design several games to explore and address specific attributes they felt were underserved in the market relative to the enjoyment potential. This was also used as an opportunity to examine the process of prototyping itself. In the process of designing and prototyping these games we accomplished goals we didn’t anticipate, which are also shared herein.

We divided and conquered to both progress the design of three games members brought in as well as to invent several new games from whole cloth. We started off in a group identifying promising mechanics, which are listed in a convenient form in this document. We conducted a “mini Horseshoe” process to divide into teams to tackle the designs. We touched base periodically to help one another progress their topics including playtesting prototype games. We consolidated results and learnings in this document. Best of all, all of these games are available to play tonight (when it’s game-playing-time a-a-t Horseshoe).

Table of Contents

1. Mechanics

2.

Games

2.1 Oh, Snap!

2.2 Horseshoe Poker

2.3 Machine Mayhem Arena

2.4 Dead Runners

2.5 Our Town

3.

Prototyping Pro-Tips: "Show the Fun"

This section lists out the mechanics the group was excited to explore in game designs. It is not meant to be an exhaustive list of all possible mechanics by any means - just interesting ones we wanted to explore.

- User Generated Content -- giving players avenues for expression and creativity

- examples: the card descriptions in Dixit, the sayings you make up in Wise and Otherwise

- Auctioning

- example: bidding for tiles in Ra or Vegas Showdown

- Permanence -- information that persists across multiple plays of a game

- example: the stats you write on the board of Risk Legacy

- Co-opetition -- games that combine elements of cooperation and competition

- Simultaneous Play -- players making moves at the same time instead of waiting for each other to go

- examples: the placement of your ships in Light Speed, Yomi

- Asynchronous Play -- taking turns, with an indeterminate time between turns

- examples: Draw Something, Scrabble

- Asymmetric Games -- players have different starting conditions, powers, etc.

- examples: Yomi, the three races of Starcraft

- Double-blind -- Players finding each other in the dark

- example: the Ravensburger game Curse of the Mummy (German name), Pyramid (U.S. name)

- Hidden Objectives -- players don’t know each other’s short term or long term goals

- example: the route cards in Ticket to Ride, the winning conditions in Fluxx

- Most/All Info Public

- Large Form Games (>8 players)

- example: Werewolf, GameLab’s GDC games

- One-directional Info -- I know something about you that you don’t know that I know

- example: Diamond Trust of London

- Cooperative Games

- example: Pandemic, Forbidden Island, Knizia’s Lord of the Rings

- Traitor -- a cooperative game but where on player is secretly an enemy

- example: Battlestar Galactica, Shadows Over Camelot

- Variability in Gameplay -- widely different setup conditions makes the game very different from play to play

- example: choosing 10 of the 25 kingdom cards in Dominion, or the random setup of the rear row of pieces in Fischer Random Chess

- Short Compounding Decisions -- small decisions early in gameplay compound to create very different late-game experiences for different players

- example: 7 Wonders, Puerto Rico

- Comeback Mechanic -- games that make it possible, if unlikely, to come back even if you are well behind

- example: Puzzle Strike, turning in card sets in Risk

- Games You Can Drop In and Out Of

- examples: Online Poker, Apples to Apples, Ricochet Robots

- 15-minute Games

- Physical Gameplay

- Collectibles and Scarcity

- High Replayability -- a game you can play for 10 years and it remains fresh and interesting

- Indirect Control -- you are making a decisions about an entity that you may or may not ultimately control

- example: Imperial 2030, Acquire

- Board Game Metastructures

- example: Magic tournaments

- Rewarding Game Master Experiences

- Gambling/Betting

- Strategy with Highly Random Elements

- examples: the dice rolls of Yspahan and Kingsburg

- Simple -- games that can be learned in a minute

- examples: Apples to Apples, Trivial Pursuit

- Negotiation -- social discussions between players

- examples: Diplomacy, Werewolf, trading in Settlers of Catan

- Narrative Context

- Knowing My Friends

- examples: Apples to Apples, The Newlywed Game

- Cinematic/Heroic Moments

- Arkham Horror, playing a “coup forre” in Milles Bourne

- Counters

- Puppeteering -- Controlling units anonymously

- Tactility -- game pieces that are a physical joy to touch and manipulate

- Memory -- games that require players to remember information

- Progressive Decks

- examples: the escalating values of power plant cards in Power Grid, the escalating costs and rewards of each round’s deck in 7 Wonders, the escalating values of room tiles in Vegas Showdown

An insulting ad-lib party game

Players: 3+

Key mechanics explored: simultaneous play, 15 minute sessions, drop-in possible

Who: Steve, Bob, Tim, John

Build

- Print Rules

- Print / create decks

- 100 Insult cards with blanks left in the insults for (nouns) and (adjectives)

- 200 Noun cards

- 200 Adjective cards

- 30 Voice cards

- 10 “Oh, Snap!” cards

Setup

- Shuffle and arrange decks

- Deal to each player: 1 insult card, 5 noun cards and 5 adjective cards

Play

- The tallest player becomes the first player and pairs with the player on his/her left. Other players pair up clockwise around the table.

- Each player selects noun and adjective cards from their hand, as indicated by the requirements on the insult cards, to form an insult

- When everyone is ready, the first player turns over a card from the voice deck, and insults the player on his left using that voice. That person then draws a card from the voice deck and insults the first player back.

- Everyone else in the game votes on which insult was better. The winner keeps the insult card as a trophy, and it is used at the end of the game for scoring.

- Used cards are placed in their respective discard piles.

- Play progresses in pairs around the table until everyone has been insulted.

- At the end of the round, everyone draws a new insult card and as many adjective or noun cards as they used during the round.

- For each next round the pairs shift by one in a clockwise direction, so that the person to the left of the tallest person becomes the first player.

- Oh, Snap!

- If a player has a rare “Oh Snap” wild card, after the insults have been traded, but before the judging takes place, the player can play that card for an automatic victory.

- After yelling “Oh, Snap!”, use the comeback on the Oh Snap card, or feel free to improvise.

- Another Oh Snap! card can be played in response to an Oh Snap!

- (The judges may proceed to vote on who would have won, but the player of the Oh Snap! card retains the trophy card, regardless of the vote).

- End condition:

- The game ends when one player has collected 7 trophy cards.

Alternative

“Mob Libs” is another Mad Libs-inspired game, with some similarities to “Oh, Snap!” After working on this for a while, we decided that “Oh, Snap!” was a more promising direction, and stopped working on “Mob Libs”.

One player is the moderator for the round. Each other player draws 5 NOUN cards and 5 ADJECTIVE cards. The moderator selects one of the stories, which is a well-known piece of text with missing words, Mad Lib-style.

The moderator reads the story until he comes to a missing word, saying either “noun” or “adjective”. Each player selects their choice of that card from their hand, showing it to the moderator but not to each other. The moderator then picks the best choice and fills in that word in the story. The winning player keeps that card, face down, to signify that he or she just won a point. The other players discard their losing cards. All players then draw back up to 5 NOUN cards and 5 ADJECTIVE cards.

Play continues until the story is completed. The moderator then reads the completed story from the beginning.

Here’s a sample completed story from a playtest of “Mob Libs”:

People will come, Ray. They'll come to Iowa for reasons they can't even fathom. They'll turn up your Mother’s nose not knowing for sure why they're doing it. They'll arrive at your door as innocent as Adolph Hitler, longing for the past. "Of course, we won't mind if you look around", you'll say. "It's only $20 per Penis". They'll pass over the money without even thinking about it: for it is money they have and Clothing they lack. And they'll walk out to the bleachers; sit in shirtsleeves on a Bloody afternoon. They'll find they have reserved seats somewhere along one of the Superfund Sites where they sat when they were children and cheered their heroes. And they'll watch the Fake Titties and it'll be as if they dipped themselves in Golden waters. The memories will be so Vomit-Inducing they'll have to brush them away from their faces.

A clever twist on poker

Players: 2-5 (3 seems ideal)

Key mechanics explored: simultaneous play, 30-min sessions, logic/strategy

Who: Tim, John, Mike

We wanted to explore making a game that is relatively quick and easy to set up, learn, and play, yet offers depth of strategy more reminiscent of German board/card games than more mass-market U.S. games.

We drew inspiration from 7 Wonders, a favorite among the design team. Specifically, some of us liked the card drafting model (there were dissenters in the group on this mechanic), and in particular we wanted to explore the introduction of a counter-force during the draft: rather than simply selecting a card to play, players would choose between paying to play a card or being paid to consume a card out of play. We viewed the 7 Wonders goals as structurally appealing with the disadvantage of being overly complex for easy digestion and optimization in a social group play setting. So, simplification was a goal.

We started with a deck of cards, thinking it would simply power an initial brainstorming exercise by providing a convenient symbolic abstraction; once we had the basis for mechanics and systems we would choose a narrative metaphor within which to iterate on the specifics of design. We were pleasantly surprised to find that it was actually a convenient end state for the metaphor as well - the advantages of the built-in familiarity players would bring far outweighed the benefits of a more creative narrative/brand. Layering on branding and expansion rules is a potential future exercise, whether that is for a commercial version or a series of expansions.

Thus, while it wasn’t an initial goal, we were very excited to have invented a fun game that can be played with a normal 52-card deck and a basic set of poker chips, and that largely leverages the in-built understanding people have of poker.

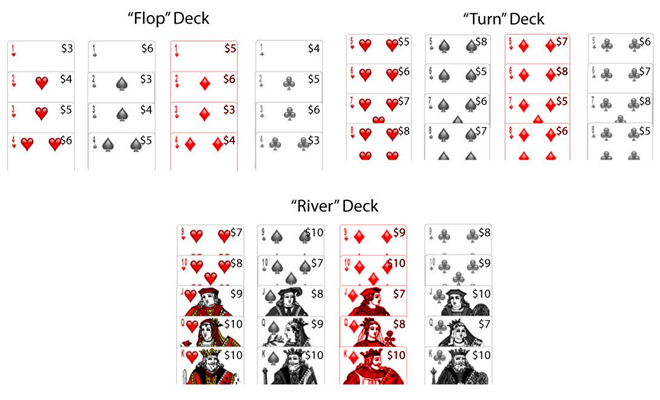

Build

- Print Rules

- Print Scoring Sheets

- Poker chips in $1, $5 and $10 denominations

- 5 random coins to be used as secret indicators (heads/tails under a card)

- Standard 52-card deck, with its cost in both upper-right corners as follows:

Setup

- Shuffle the River Deck

- Shuffle the Turn Deck, place it on top of the River Deck

- Shuffle the Flop Deck, place it on top of the Turn Deck

- Deal from the top, 3 cards to each player

- Each player starts with $5 in chips

Play

- Each turn:

- Draw a card

- If there are not enough cards for all players to draw then no one draws a card.

- Play a card

- You GET PAID TO PLAY the lowest-cost card in your hand (there may be several to choose from)

- Otherwise, you must be prepared to pay the indicated cost to the bank

- Place the selected card face-down over the secret indicator, tails-up if the card is free else heads-up

- When all players are ready (have a card face-down on their tableau), reveal the card into your tableau

- Pay the card cost indicated to the bank if the marker is heads-up, else receive the indicated cost from the bank

- If the card played results in a set of 2+ cards of the same rank (e.g., Q-Q) receive money from the bank equal to the price of the highest cost card in the set

- Pass your remaining unplayed cards face-down to the player to your left

- End condition:

- The game ends when players pass exactly 1 card; this last card is discarded unplayed

Score

- 1 Victory Point (VP) for each $4 in cash, rounding down

- 3 VP for trips (e.g., 8-8-8)

- 6 VP for quads (e.g., K-K-K-K)

- 1 VP per card in your largest flush

- 1 VP per card in each 3+ card straight

- 1 VP per card in each 3+ card straight flush

- Bonus

- 3 VP for player with the largest flush

- 6 VP for player with the longest straight

- Bonus points are divided amongst winners in the case of a tie (round down)The player with the most VPs wins

Possibilities

- Advanced Features

- Switch hand passing order when the first 7 is played (again on next 7, etc.)

- Hidden goals

- Tournament Rules

- Play <n> rounds

- Changing seating order

- Rather than score money, start next round with previous round cash remaining

- For a “retail” version

- Flop / Turn / River decks indicated by different colors/symbols on the fronts (to protect info before reveal)

- Themes alternative to the classic suits (meaningful to the hidden goals)

Perfect information bluffing board / card game

Players: 2 per battle, but groups may drop in and out

Key mechanics explored: Permanence, Metagame / Negative Feedback Loops

Who: Zack

Each player owns one or more robots. The player's goal is to defeat other robots to have the most famous robot fighter.

The game takes part in two phases: battle and garage.

---------

BATTLE

---------

In battle, each player brings one robot card, twenty energy tokens, one screen and the associated upgrades and malfunctions with the robot. In addition, some damage tokens are available for both players. Three Upgrade cards are dealt from the upgrade deck to the side.

A turn starts when each player selects a number of energy tokens to use that turn. A player may choose to use zero energy. He puts those tokens above his robot card and an upgrade he plans to use that turn if any. A player can use zero or one upgrades per turn. He places the remaining tokens and unused upgrades below the robot card. Both players then raise their screens to reveal the energy they used.

Take the robot's upgrades into effect and compare the energy each player used for the attack. The player who used the most scores a hit (unless the relevant upgrade rules say otherwise). If the robots tie in energy use, they simultaneously hit each other. Each time a robot takes a hit, give it a damage token.

If a robot takes five hits, it is knocked out. If there is only one robot remaining, it wins the battle!

The player's available upgrades, malfunctions, damage and energy levels must be supplied upon request.

-----------

GARAGE

-----------

At the end of battle, you must repair your robot. Remove the damage tokens and punch a hole in the robot card for each damage token removed. A robot must have at least one repair space available to battle. When a robot can no longer battle, retire it and admire its many victories.

For the winning robot, mark a victory on its Wall of Fame. Write the name of the opponent and the date of the defeat. If the robot took any damage in that win, it must also take a malfunction from the malfunction deck.

After battle, trace a circle on the robot's money track. If the robot won, trace a second circle.

In the garage phase, starting with the losing player*, players may spend any robot's money to buy one or more of the available upgrades for that robot. The player may only buy the upgrade with the least amount of wear marked on the card. Fill in the number of traced circles equal to the cost of the upgrade and pair the card with the robot. Then increase the card's wear by one. When the losing player is done, draw back up to three upgrades face up on the table and any remaining player may buy upgrades.

*If both players lose or if it a player's first game of the session, play paper-scissors-rock for the right to go first.

---------------

ROBOT CARDS

---------------

Robot Cards have 4 zones:

On the left, twenty repair marks.

On the bottom, a number of money circles.

On the top, a blank for the robot's name and picture.

On the right, an area for the robot's Wall of Fame.

A robot starts with three cash.

-------------

UPGRADES

--------------

Some upgrades are used every turn. These cards will say "Every turn". Some have the word "exhaust". These upgrades can only be used once per battle. Some upgrades have the word "destroy". These can also only be used once. When an upgrade is destroyed, put it on the bottom of the upgrade deck.

Shiv (1) - Exhaust before reveal. If there is a tie this turn, you do not take a hit.

Judo Training (2) - Exhaust before reveal. If the opponent outspends you on energy this turn by three or more, you win the point instead.

Overclock (2) - Exhaust after reveal. You may revise your energy selection higher. You must pay the difference plus two energy. (If you overclock from 1 to 5, you must pay 7 total for the turn, 5 for the new energy level and 2 for the overclock)

Feint (2) - Exhaust after reveal. You may revise your energy selection lower. You must pay two energy plus your new energy level.

Deflector Shield (4) - Every turn, if the opponent's energy spend is one higher than yours and if you have spent two or more energy this turn, consider it a tie.

Advanced AI (4) - Exhaust before reveal. If both players reveal the same amount of energy, the opponent takes an additional hit.

Smoke Screen (4) - Exhaust after reveal. Adjust your energy spent this turn up or down one. You must spend or gain that extra energy, respectively.

Missiles (6) - Exhaust before reveal. If you hit this turn, deal an additional hit.

Charge Cell (6) - Every turn, before reveal, move one energy from your stock to this card. If this card has six or more energy, you may destroy this to deal your opponent two hits.

Spiked Shell (6) - Exhaust this on a round that you spend zero energy. Next turn, you gain two energy that you must spend.

Bait (6) - Exhaust before reveal. If you are hit, the opponent must take a hit.

Fuel Cell (8) - Every turn, if you are not hit, gain an energy.

Self-destruct Button (1) - If you have four damage tokens, destroy before reveal to take a hit and deal three hits to the opponent.

Fight or Flight System (3) - Every turn that you have four damage tokens, you gain one free energy.

Rocket Boost (1) - Destroy before reveal on your first turn. If you hit the opponent, he takes an additional hit.

Self-Repair Kit (2) - Destroy before reveal. Remove a damage token from your robot.

Shield (3) - destroy before reveal. You can neither hit nor be hit this turn. Lose one energy per hit you would have taken.

--------------------

MALFUNCTIONS

--------------------

Energy Leak - When you get hit, lose an energy.

Loose Screw - You may not play one energy.

Stuck Gear - You may not play zero energy.

Bent Metal - All upgrades cost 1 money more.

Feedback Loop - If you can use an upgrade, you must. ( Max 1/turn).

Dented Hull - You start with one damage token.

Friction - You may not play four or more energy.

Broken Port - You may only bring one upgrade into battle.

Voice Modulator Bug - If the robot's owner says the word "the" while in battle, his robot takes a hit.

Drained Cell - You start with two less energy.

Inefficient Cell - You start with one less energy.

Floating Point Error - When you and your opponent reveal odd numbered energy, lose two energy.

-------------

DESIGN NOTES

-------------

Permanence

Negative Feedback Loops

Largely Luck-Free

Drop Out / Drop In

Zombie Card / Board

Players: 2-6

Key mechanics explored: Cooperation, Cinematic Gameplay, Better GM Experience, Variability in Gameplay

Who: Coray Seifert

Synopsis

Dead Runners is a concept I’ve been playing with for years, but never made much headway on. I can to Horseshoe this year with a fantasy in the back of my mind that I would stay up all night, finish some piece of it, and have something to show for it. This year’s Paper Jam completely blew my mind and the outstanding talk by David Sirlin about minimalist design gave me the clarity to gut the existing design and go after a more elegant core mechanics paradigm, while preserving the fundamentally massive form of the game.

Process

Coming into Horseshoe, I had an introduction and a long bullet list of features, ideas and loose concepts. The first thing I did was take an axe to that list, rolling everything into a core Arkham-Horror style combat and exploration mechanic, combined with board building elements from many popular co-op games. My goal was to create a quick prototype, but I quickly lost myself in the beautiful process of creating content, printing and designing cards, and all that fun stuff.

The Dead Runners Core Rule Set

I happily share my progress on the game with the community. I do plan to continue development on this, so I ask that you not steal the idea without at least sending me a fruit basket. If you have suggestions for where to take it, or you’d like the materials to print your own copy out for playtesting, please email me! I’d love to share.

Dead Runners

You wake in a hospital bed, an IV attached to your arm, coughing out an intubation tube. The intensive care unit is empty, gurneys and operating tables askew, the doors crudely boarded up. To your left and right, bewildered survivors awake from their stupor. The backup generator shutting down cut off their oxygen supply as well, shocking some to life, and sparing others the horror that you will soon face.

Dead Runners is a cooperative game where players work together to escape a sudden outbreak of a mysterious infection. Craft your strategy, search the ruins of New York for supplies, and watch each others’ backs, or you could find yourself standing off against a familiar face.

The Goal of Dead Runners…

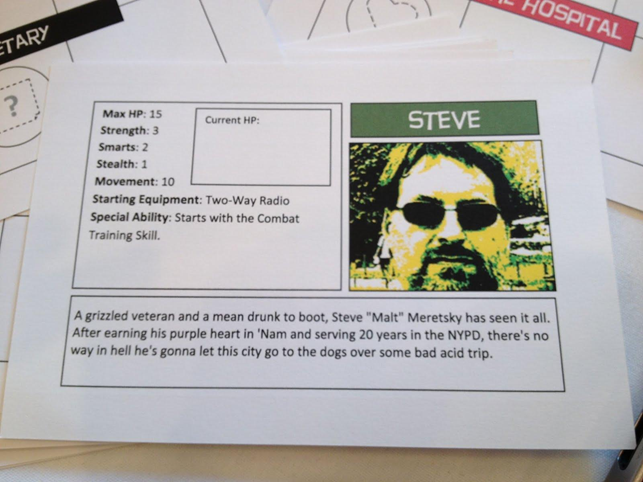

To play Dead Runners, you will need two or more players. At least one player must play as a zombie. All other players play survivors.

For the survivors, the goal of Dead Runners is to survive the Zombie Apocalypse that has gripped the streets of New York City, by finding a way out of the city, finding a cure to the plague, or surviving until the military can save you.

For the Zombies, the goal of Dead Runners is simple: KILL THEM ALL.

Setup

- Find a dark and scary place. A post-apocalyptic metropolis or creepy basement is ideal, but use your best judgement.

- Lower the lights to the minimal value necessary to read the cards. Ideally, the flickering light of a candle or oil lamp.

- Turn on creepy, intense music.

- Divide up all cards into their respective stacks.

- The player who won the last game, survived the longest, or was most recently sick (in that order) is the starts off as a Zombie. All other players are Survivors. The player playing the Zombie must leave the room and come back in-character (see Zombie-Survivor Etiquette on page 3).

- Each survivor draws three characters and picks one to play this game.

How To Play

- Place the hospital tile.

- Survivor furthest from the Hospital goes first, going clockwise around the table. If it’s a tie, the person clockwise from the Zombies goes first.

- Survivors move, up to their Movement.

- Survivors declare actions (search, attack, or use an item).

- Survivors resolve actions.

- Zombies draw cards (1 in Act 1, 2 in Act 2, etc.). The zombie with the fewest cards on the table goes first, going clockwise around the table.

- Zombies move any Zombies on the board, up to their Movement.

- Zombies declare actions.

- Zombies resolve actions.

Exploration & Searching

Players wake up and are unfamiliar with their surroundings. Once they reach the edge of a tile, they reveal the adjacent tile, pulling a tile from the top of the corresponding act deck.

Players place equipment tokens on spots as designated by the location tile. These tokens indicate places where players can search to find equipment that may help them survive. Once a tile has been searched, it is taken off the board.

Icons indicate what type of equipment could be found in that location:

Equipment types:

- Medical

- Military

- Information

- Supplies

Decks

- Character Cards

- Act Cards

- City Tiles (by Act)

- Zombie cards (by Act)

- Equipment cards (including mission cards) (by Act)

Zombie-Survivor Etiquette

Survivors and Zombies should never sit on the same side of the table, nor exchange pleasantries for the duration of the game. Survivors should view zombies with a combination of disgust, hate and pity. Zombies should view survivors as a delicious snack.

Survivor Death

When a survivor is killed, they leave the room, and come back after composing themselves and getting into character. They spit. The drool. They hiss. They join their zombie brethren at the table and get ready TO FEAST.

3-Act Structure

Players draw cards from the various decks in the game based on what Act is currently active. Specific cards in the Zombie deck will cue new acts. Once that happens, draw from the new Act pile.

Each act follows this model for balancing base cards, special cards and all-powerful uber cards:

Act I

o Base – 95%

o Special – 5%

Act II

o Base – 80%

o Special – 15%

o Uber -5%

Act III

o Base – 50%

o Special – 30%

o Uber -20%

Combat

Combat is very simple:

- A player declares they are attacking another player

- Player rolls the d100. If they roll under the “Chance to Hit” number for that weapon, they hit.

- Note that defenders may have cards that reduce an attackers Chance to Hit.

- The player rolls damage based on the Damage rating for that weapon. That damage is removed from the target’s remaining hit points.

- If the player deals more damage than their target’s remaining hit points, they kill it.

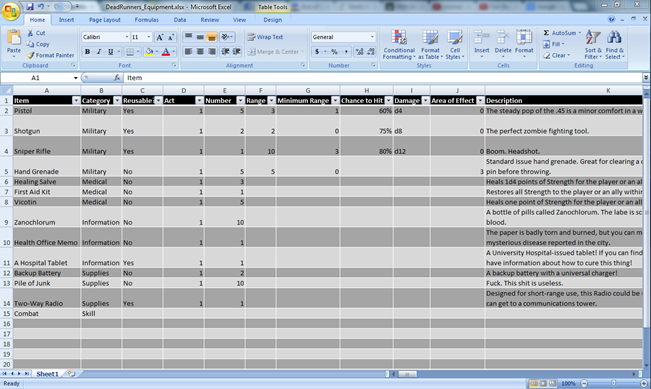

The remaining content for Dead Runners is held in content sheets, like this one, for easy sorting and data manipulation. I know some folks shy away from

Interesting Notes & Lessons Learned

Printing on Cardstock is Great...

Creating everything in word and then printing onto heavy cardstock created a great, tactile feel for the cards. It gave the game a sense of weight and made it real. Folks look at cards like these and even though they are in wireframe format, they know what they’re getting into:

...but Takes Freakin Forever!

Also, cutting circles is hard. Consider using hexes next time.

Giving the Game Master a Player Role is Awesome

Having a real-life player dedicated to taking an opposition role in a game provides incredible gameplay diversity, replayability, and depth. However, the game master role is often difficult, incredibly time consuming, and can be less rewarding than a traditional player experience.

Digital games like Left 4 Dead and Natural Selection have done a great job of creating player roles for those playing in a game master-like role. In Dead Runners, I borrowed from a classic swimming pool game called Sharks and Minnows, where a single Shark player faces off against all other players, who are Minnows. The Minnows attempt to cross the pool underwater, while the Shark attempts to pull them to the surface and tag them on the head. The key is that when the Shark tags a Minnow, that Minnow becomes a Shark in the next round.

It’s both a great example of player-managed difficulty and also gives the game master (in this case, the Shark) a very rewarding role, while offering many people the opportunity to share the game master load.

Offloading Complexity from Core Systems to Content Increases Accessibility while Preserving Depth

I wanted this game to be huge. A big, nasty, Arkham Horror-style game where players can invest in a strategy early (focusing on skills, equipment, or information) and see their results play out over the entire gameplay session. While this did necessitate a very broadly scoped game, the core rules are very simple, with the desired one-off experiences and mechanics (finding a clue, fighting a zombie, being a hero) largely living in the descriptions of the various items, characters and events in the game.

This allows players to jump right in, start playing immediately without having to memorize a number of rules sub-systems and special cases, and then address those special cases at the moment they are relevant.

A Personal Note

In my 10 years in the games industry, I’ve been to a number of fantastic games industry events. 9 or 10 GDCs. Countless IGDA events. Various other E3s, Summits and Forums.

This sessions was far and away the best conference session I have ever participated in. To be able to sit in a room with some of the greatest minds in our industry exploring new game mechanics without the confines of traditional commercial development was like a hug from a game design rainbow. Turning to someone like Mike Sellers or David Sirlin and breaking through a roadblock in 15-20 seconds or hearing Bob Bates and Steve Meretsky testing their game a table away is a once-in-a-lifetime experience and I’m thrilled to have had it this weekend.

I’m already looking forward to Paper Jam 2013, and I thank my fellow Paper Jammers for a wonderful, productive, awesome session.

Community-builder card/board-builder

Players: 2-6

Key mechanics explored: Co-opetition, Negotiation, Hidden objectives, 1-Hour Gameplay

Who: Mike Sellers

Synopsis

Our Town is a game about creating a small town community. Each player represents a group or faction in the town focused on increasing wealth, cultural unity, or the people’s happiness. Each player tries to maximize their own goals while also keeping the community alive and thriving.

Beyond the overt gameplay this game is meant as a quasi-educational vehicle to teach people about the struggles inherent in keeping a community together while each individual also pursues their own goals. The game features strategic trade-offs, income accumulation, individual and group action to resolve unpredictable events, and many opportunities for negotiation as the players work to grow their small town.

The winner is not known until the end, but along the way it is possible for everyone to lose if they allow the community to disintegrate.

Components

- Three decks of cards:

- Goal cards

- Buildings and roads that are built during the game

- Events and Heroes that happen during the game

- Value Tokens: There are three Values that players are trying to maximize.

- Happiness: how satisfied the residents are with their lives, families, and social connections

- Wealth: trade, physical support of individuals and families, and accumulation of material wealth

- Culture: a shared sense of identity, place, and purpose between people

- Community Token Pools: The community has pools of each of the three Value tokens. If any one of these drops to zero at any point during the game, the community has disintegrated and all the players lose.

- Player Token Pools: Each player has zero or more of the three types of Value tokens. Each player is trying to maximize one or more of these Value tokens.

Goal Cards

Each player is trying to meet their own faction’s goals, while also trying to build the community. Each player will have a Goal Card that says how much of each currency they are trying to accumulate before the end of the game.

Building & Road Cards

- Roads must connect to other roads.

- Intersections can be played over a road card, but not immediately adjacent to another intersection (there must be at least one road card between them).

- Some roads also contain things like plazas, fountains, and statues that may generate income for the owning player in value tokens (see below).

- Buildings must be played next to one or more roads. In some cases (shown on the card) buildings may be played on top of other existing buildings.

- Buildings and Roads each have a cost that must be paid when they are played.

Event & Hero Cards

Events are played off to the side, and remain in play until their condition is resolved (see below).

Heroes are also in the Event deck. A hero may be drawn instead of an Event. These cards may be brought into play if their cost is paid. They typically have a positive effect. Hero cards may also be used to resolve an Event by “covering” the Event and thus removing both from the game, rather than paying the typical Event resolution cost.

Game Start and Play

Oldest player goes first, proceed in clockwise direction.

Draw Goal Cards: Each player draws three goal cards for their chosen faction and keeps one. The others are discarded from the game. This card has conditions that yield victory points at the end of the game: having an amount of one, two or even three currencies, building a certain building, etc.

Take starting Tokens: Each goal card specifies a number of tokens of each type that the player starts with, and how many of each type are placed in the Community pool.

Draw Building Cards

Each player begins a hand of 5 cards. Each turn a player must pick a new card and play a card (unless they have a card that allows more or less than this) each turn.

Playing the Game

Starting with the oldest player and going clockwise, the first player who has a four-way intersection plays this card at no cost. This player then draws a card and plays a card and play continues in a clockwise direction.

During the game, at the end of the last player’s turn, all the buildings and roads that generate Value tokens have these replenished. An Event card is then drawn (see below).

Adding Roads and Buildings

On each turn a player may add a road or a building by playing a card from their hand.

Each road and building has a cost in Value tokens: Happiness, Wealth, and Culture. The player pays this cost when constructing the road or building. The card indicates whether the cost is paid to the community pool or to a general/unused token pool (road cost is typically paid to the community, while many buildings are paid to an unused pool).

If the player cannot pay the cost, then he or she may negotiate with others to pay for part or all of it. In such cases the other players may gain co-ownership or receive some other benefit; whatever the players decide is up to them. If a player cannot pay the cost even after negotiation, the card may not be played.

When a player plays a structure that generates Value tokens, he or she places a piece of his or her color on it to indicate ownership. Some structures may belong to the community; all tokens from such structures go into the communal pot.

Replacing Buildings

A player may replace any buildings they own with another building they are constructing. In some cases (e.g. with roads), a building may be placed over a specified pre-existing one.

Buildings Change Ownership

Players may sell buildings they own to another player for any amount of any mix of the three currencies that they mutually agree on. Players may have as a goal the control of a particular building by the end of the game, and so will be motivated to purchase it if they cannot build it. Some Event cards may also transfer ownership between players.

Building Benefits

Each building generates one or more of these values for its owner (the player who played it, unless it changes hands) each turn.

Some buildings also have a running cost in tokens that must be paid each turn. If a player cannot pay the cost, the building may change hands.

Player Token Pools

Players keep their own pool of value tokens, and together keep a pool that belongs to the community. To build a building or resolve an event, a player may play the necessary tokens from their own pool, combine with another player’s pool if they can make a deal with that player, or draw from the community pool if all players agree. If a deal is struck between two or more players, it is up to those participating to decide on the terms of the deal.

On each player’s turn, the player collects Value tokens from each structure they own that generates them. They may also have to pay tokens to satisfy that building’s need, shown as negative income.

Events

An Event card is drawn once every round at the end of the last player’s turn. In some cases, an additional card must be drawn if a building card requires it as a condition of constructing the building. The Event is played face up and takes effect immediately.

Some Events have a set of necessary conditions that must be met before they can be played – a certain building must be in play, the community pool must be of a certain size, etc. If this condition is not met, the card is cut into the middle of the deck and a new Event card is drawn. Repeat once for each player in the game, or until an Event that can be played is drawn, whichever comes first.

Each Event has resolution conditions: a certain amount of value tokens that must be paid, a building that must be put into play or removed from play, etc.

- If there are tokens that must be played, any or all of the players can draw from their own pools (as they agree), or if they all agree they may draw from the community pool of tokens.

- Players vote by spending Culture currency.

- Players may negotiate with each other (openly or secretly) to trade off currencies (or for control of buildings, cards, etc.). For example a player with a lot of Wealth can trade their Wealth with another player who has a lot of Culture to gain that influence.

- Voting is done simultaneously after all negotiation is complete (players are encouraged to set a time limit on negotiations).

- If there is a building that must be played and a player has it in their hand, they must play it.

- If two or more players have a building that must be played in their hand, the player who will have their turn soonest gets to play it – but they may strike an agreement with one of the others to do so instead if they like.

- If two or more players own a building that must be removed, the player who will have their turn soonest must remove it – but they may strike an agreement with one of the others to do so instead if they like.

Each turn that an Event remains unresolved it remains in play. On each player’s turn the Event has its effect on the community – draining Value tokens from the community or from one or more factions for example. Once the Event is resolved (paid for) it is removed from play and placed face up on the bottom of the Event deck. When the Event deck is exhausted it is reshuffled.

Game End

Winning the Game: When all the building and road cards have been exhausted, the game is over. At this point each player counts the number of each type of token in their pools and (if needed) which buildings they own. These are compared to the goals listed on their goal card and scored as shown on the card.

The player with the highest number of victory points wins. In the case of a tie, the player with the most tokens overall is the winner. If there’s still a tie, everyone gets ice cream.

Losing the game: if any one of the Value pools for the community ever drops to zero, the game is over and everyone loses. (Easier variant: two pools must drop to zero.)

We wanted to use this opportunity at Project Horseshoe to not only focus on quickly designing new games, but to explore ways to effectively prototype them as well. In conversations within the Paper Jam group and with those in other groups at Project Horseshoe, an outline of effective prototyping practices became clear as discussed here. However, this discussion and list are not exhaustive and deserve additional exploration.

Purposes of Prototyping

Game prototyping is a critical step early in a game’s design. Its first key result is to see if the game as imagined is actually fun. The prototype may be extremely rough in its look and incomplete in terms of units and data, so long as it is possible for those other than the designer to experience and evaluate the game.

While a game prototype exercises and explores the game’s rules and interactions, that is not its main purpose. The main thing the prototype must accomplish is to communicate the intent of the game to others. In MDA terms, the prototype should explore the game’s mechanics (which often emerge directly from the design document), identify interesting dynamics, and most of all show the game’s aesthetics -- its heart and soul, the feelings the players will experience, and the reason the designer is passionate about the game in the first place.

The other primary purpose of prototyping is to assess the game’s overall viability in terms of gameplay and ultimately commercial salability (whether a board game, retail computer game, free-to-play game, etc.).

Convergent Iteration

It is often the case that a game as imagined is not fun when first prototyped. However, this does not mean the game idea is no good; subsequent fast prototyping iterations can often converge on solid gameplay in a concept and thus “show the fun” to those not involved in the game concept. It is also sometimes the case that an idea simply will not gel into a worthwhile prototype. In such cases, it may be that the idea simply isn’t viable in its current form, or that parts of it can be extracted and used as part of other game designs.

The question of how long to prototype on a game concept is a difficult one to nail down. The general sense is that for a modern online game, 1-3 months is a useful minimum, and 6 months is a likely maximum. At some point during that period, the designer(s) in charge of the prototyping should either be able to “show the fun” to others in a clear (if still rough) fashion, or they should be able to step back and agree that the current effort is not worth pursuing. The ability to know when to persevere in the face of iterative failure or to back off when a game is not coming together is one key mark of a senior, seasoned game designer. This is the a combination of following your intuitions to a useful, viable idea and not becoming stuck on the preciousness of your own idea.

Pro-Tips

A number of heuristics and pieces of advice came out during our discussions. Some of these are listed as Dos and Don’ts below:

Do:

- prototype and play fast: for a card game, in the first hour. For a computer game, in the first day or two.

- try to create all the “columns” -- the attributes for game objects

- choose a few key moments of gameplay to show

- look for interesting interactions between mechanics that make the game more fun

- identify places where the game doesn’t work and ruthlessly weed them out

- iterate as fast as possible

- listen to the experiences of those playing the prototype

- remain true to the initial game concept -- until you find something better

- know when a game isn’t coming together and let it go

Don’t:

- worry about the “rows.” Beyond a few archetypal examples of the nouns you’ll be using in your game (card types, tile examples, etc.)

- prototype the introduction or tutorial of the game - jump right into the action

- try to give the player the complete experience of playing the game (unless the game is very simple or repetitive)

- try to show the final or climactic moments of the game

- try to create all the objects needed for playing the actual game

- worry about art beyond the barest minimum to communicate the game’s intent

- be reluctant to kill or restructure major parts of the game

section 9

|